Hello dear

readers!

This post is

a small synopsis of my experiences so far as a student in this years Summer of

Code in Space, where I shall recount the whole adventure of integrating

Sentinel-2 data into Marble Virtual Globe.

Sentinel-2 data.

So what exactly is this data, and why is it important to us?

Well, Copernicus is the worlds largest single earth observation programme directed by the European Commission in partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA). ESA is currently developing seven missions under the Sentinel programme. Among these is Sentinel-2, which provides high-resolution optical images, which is on one hand of interest to the users of Marble and the scientific community as a whole.

Our goal

with this years SOCIS was to adapt this data into Marble. Since Marble has

quite the track record of being used

in third party applications with great success, this would essentially be a

gateway for many developers to get easy access to high quality images through the

Marble library.

So first

order of business? Adapt the world. The summer has begun to get exciting.

First Acquaintance with Marble

Of course,

nothing can happen so quickly, and the first task was obviously on a smaller

scale. In order to familiarize me with the inner workings of Marble, my mentor

gave me a task to adapt an already available dataset into a map theme for

Marble. This is how I came to know TopOSM.

The TopOSM maptheme in Marble.

This task came

with its own fair share of challenges, from getting Marble to display the

legend icons correctly, to creating a suitable level 0 tile, but in the end it

did give an insight into exactly how the creation of a map theme, from the

first steps to uploading goes. At this point, the challenge was underway, and

so began the real part of our ambitious project to tackle the whole world

through Sentinel-2's lens and integrate it into Marble.

Sentinel-2 - From drawing board to tilerendering

After many

discussions with my mentor, regarding ideas on how to make the data suitable

for use in Marble, we finally came up with a plan. That plan would let us use

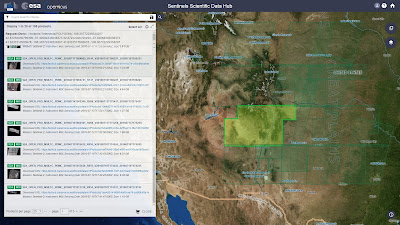

the currently available Data Hub as

a source for our images (since we don’t have a simple server we could just get

the data from, as in the case of TopOSM). At that point, we just have to edit

these images into a suitable format, and everything will be fine. A three step

process:

Step 1.

Download some data.

Step 2. Edit

it.

Step 3. Use

it in Marble.

As you may

have guessed, step 2. was to be troublesome. Around this time my mentor came up

with the first iteration of the guide for this “three-step” process. We also

found an application that would suit our needs for the editing, this was to be QGIS, but we would also be using GDAL.

The now mostly

finalized guide can be found here,

however here are the original steps:

Step 1. Find

some suitable (has few clouds, isn’t very dark, etc.) data on the Data Hub, and

download it.

This step

was to be the least troublesome, since what do you need? A good internet

connection (check?), and hard drive space, since each dataset we download is

about 4-7 gigabytes (also check). The only problem was the downloads seemed to

fail, without warning or rhyme, or reason. One could move the mouse constantly,

and it might fail, one could leave the computer unattended and the same thing

would happen, even though the last 5 datasets were downloaded without fail.

It was quite

a mystery, but thankfully the browser could restart the download (after

refreshing the page and logging in again to make sure). Another helpful site

was an archive, where some of the

more recent datasets were uploaded. These could be easily downloaded with wget

without any issues, so the troublesome downloading (the Data Hub only allows

two concurrent downloads at a time) was more or less solved.

Step 2. Edit the data.

Here's how a few tilesets look when loaded, after you applied the styles.

As any

reader may have felt profound despair at this point, so did I. My mentor most

likely as well, as we both, very rightly, felt that there had to be a better, faster, more efficient way.

Who knew

that the whole solution for all this would be a script?

So from then

out, I was knee deep in the documentation to find exactly which classes store file-saving

settings in QGis (hint: it’s this one). Applying the style was something I’ve

seen used in plugins, so that was a good stepping stone.

A second

great discovery was the fact that QGIS provides an easy way to generate the

query window (so I didn’t have to meddle with the appearance, just finding the relevant

settings in the documentation) through the processing toolbox.

Soon, the

first version of the script was ready: Load the vrts in QGIS, open the script

window, select where you want to save it, and which styles you want to use, and

presto. An hour later you might be done (with

that dataset. Onto the next!). My mentor was quite happy with the fact that

you didn’t have to sit there and apply settings every 1 to 4 minutes, instead

just once every half an hour or so (to load the next batch up). The sky, or in

this case processing power of your computer, was the limit.

The last

step in editing involves the creation of the actual slippy map tiles.

Thankfully, that was already available in QGIS plugin (QTiles), so we didn’t

have to find another way to make that. Tile creation however is a very slow

process (it takes more than a day to process about 10 datasets), so this step

is still a bit problematic. Even splitting the project into smaller sections

doesn’t do much speedwise, but it’s fairly reasonable: there are 15 levels we

need to create, with level 0 being a single image of the entire Earth, level 1

being four images, level 2 being those four split into 4 again, and you can

soon see that at level 14, there are many

tiles being generated. Such as it is.

Step 3.

Upload and use the tiles in Marble.

This step is

fairly obvious, you need to upload your freshly generated tiles onto the Marble

servers, and soon you will be able the see the fruits of your labour with your

own eyes. As of this post, more than 70 tilesets have been generated anduploaded, but there’s still a long way to go.

Concluding

For now I’m

just glad to say that I’ve had a wonderful experience this summer here at

Marble, by having helpful mentors around who welcomed me into the community,

heard all my issues and tried to support me whenever I got stuck. Overall I’m

really happy that I took part, because I learned a lot about communication,

project management, problem solving, both on my own, and with help. Of course,

this is just the beginning of everything, and I hope to become much more

productive and helpful in the future. As for everyone, I wish you all a great

summer and many great experiences to you all.